So if you’re following along, you know I have been looking at my matriarchs. But Father’s Day and all the lovely posts my friends shared about their own fathers stirred me up enough to change the progression of these posts, and today I’ll talk a little about my father and his line, the Mortensens, from Fanø, Denmark,

Facebook used to have a lovely category to describe relationships: “It’s complicated.” This is often true of one’s familial relationships, and it’s certainly true of my relationship with both my fathers, my biological progenitor and my legally acquired stepfather. Frankly, neither of them seemed to care much for me in the slightest, although neither physically abused me and in the case of my stepfather, he stalwartly took on my physical maintenance for a goodly period of time when he married my divorced mother.

A long life gives one a long time to reflect, and by now I can view my father with considerably more compassion and acceptance than I could decades ago. I can now see that he was a product of his difficult childhood and of course the difficult childhoods of both of his parents, as well as his unrealistic life expectations and then a good bit of egotism, alcohol, and sloth. Still, he’s an interesting character and his father’s line has given me a great deal of insight. So let’s begin.

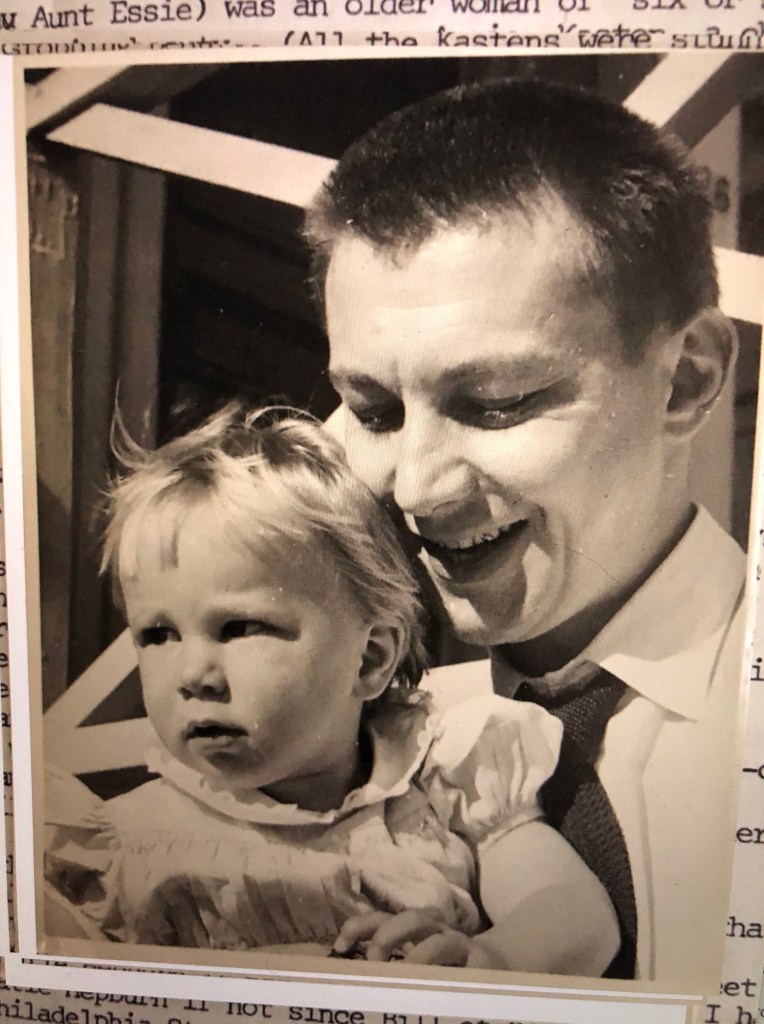

This is the only picture I have of my father and me together, taken when I was about 18 months old or so. He apparently found me amusing as a small child, since he could teach me things and I could then show off to strangers. My best party trick, apparently, since it’s the only one I know about, was to identify artists by their paintings after he drilled me on this for a while. “That’s Mr. Monet!” I would exclaim, or “That’s Mr. Van Gogh!”

Niels Laurids was born in Milwaukee, Wisconsin in 1922 to Niels Laurids Sr. and Johanne (a chapter on whom will be forthcoming). His Danish immigrant father was an engineer at Cutler Hammer, a company which specialized in motor starters. (Think the ignition in your car. Now think the control equipment for the Panama Canal, which the company oversaw.) My grandfather apparently had around 20 US patents to his name and was quite the rising star when he, almost exactly like my maternal grandfather, died at his desk in the early 1930s of an apparent stroke. Niels, at 11, and his brother Erik, at 7, were left with their mother.

My father, with his rakish good looks, expansive European vacations, and clever way with words, was quite the chick magnet in high school where he met my mother. He went off to study aeronautical engineering at MIT where he quickly disabused himself of any sincere technological interest. After being expelled for some piece of mischief or other, he next found himself at the University of Chicago studying English literature with an eye to being the next great American novelist.

Post-university, sadly, Niels’s life was a twisting tale of cruel disappointments, missed opportunities, poor choices, very occasional bright spots, and probably some serious undiagnosed mental illness (my mother tried to talk him into a lobotomy at some point, if you can believe that). So at this moment, let me leave you with a photo of Niels with his friend and colleague Alex Haley, who attributed Niels with making sure that “Roots” actually saw the light of day:

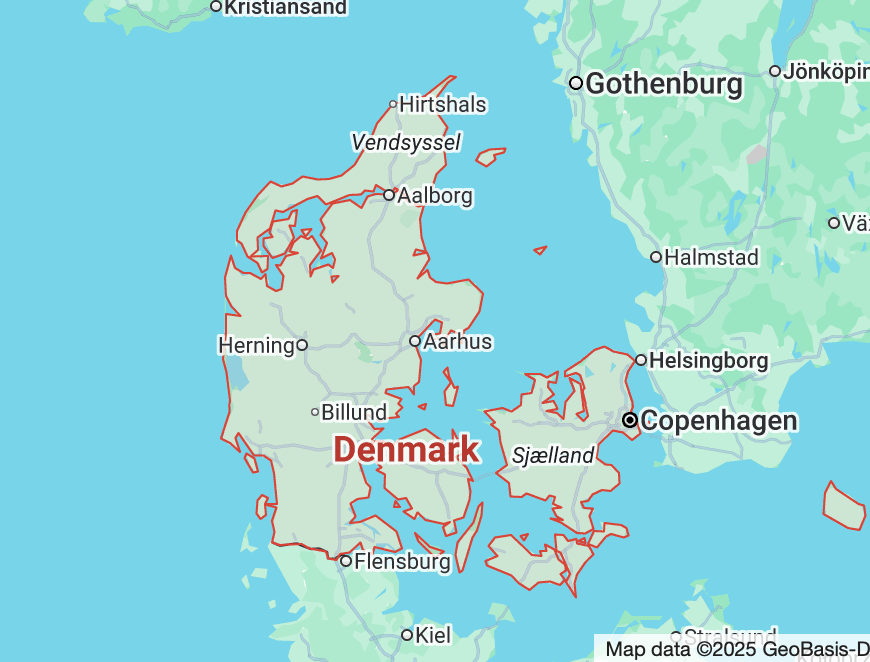

Moving back one generation, Niels Laurids Sr. was born in 1885 on the small Danish island of Fanø. Just a few kilometers off the southern Danish coast near Esbjerg (pronounced ES-bee-yow), Fanø is currently a very popular summer vacation site, known for its long kite-flying beach and lovely holiday accommodations. But the history is much more interesting and complicated than that. More in a bit. Fanø is the northern one of the two small islands that you see on the west coast just above the German border. If I could have figured out how to mark in on this map, I would have.

The first of seven brothers born to Morten Hansen Mortensen and Ellen Lauridsen, Niels Sr. was a hardworking and ambitious lad with one fatal flaw in the eyes of his family. He did not want to go to sea. Almost all the Mortensen men and their kin went to sea, and Niels’s desire to be (horrors!) an engineer was seen as basically ‘coming out gay’ in my great-grandfather’s eye. Undaunted, Niels headed south to Mittweida, Germany, where around 1903 or so he enrolled in what is now called the University of Applied Sciences (Hochschule) Mittweida, one of the largest private universities in Germany around the turn of the 20th century for machine-building engineers. He then immigrated to Milwaukee in 1906 and toiled away as a solitary Scandinavian bachelor until he met and fell in love with my grandmother Johanne sometime around 1916 or so.

The pair married in 1920 and had two sons, my father in 1922 and Erik (seen above) in 1927. In my father’s recollection, Niels Sr. always rose early and quickly left for work, returned late, and was rarely available for much interaction. That being said, my father was devastated when Niels Sr died, although during the following years before the Second World War his mother took the boys to visit Fanø nearly ever summer, allowing them to form a bond with the island and close relationships with their relatives and cousins.

Sadly, I don’t know anything more about this (to me) impressive man, no habits or preferences, no stories, no favorite sayings, no quirks. One summer my grandmother showed me his high school transcripts, his slide rule, his fountain pen, and his Mason’s pin, all she had kept of him. Sadly, even those small tangible bits of his life were lost when her house burned down in 2000, even more sadly together with my Uncle Erik.

Now we move back another generation, and here’s where my maniacal interest in genealogy offers the most clues. As I mentioned above, Niels was the first of seven brothers born to Morten Hansen Mortensen (1854-1932) and his wife Ellen Lauridsen (1858-1931):

Morten Hansen was a ship master. His father Morten Jensen was a ship captain and a miller (in the off-season). His grandfather Jen was a ship captain. His great-grandfather Morten Jensen was a ship captain. You get the drift. Of the seven brothers in my grandfather’s nuclear family, he and his brother Morten immigrated to the US; three brothers died at sea, one ran away to another city never to be heard from again, and one stayed home. And that’s not even starting to talk about the fathers/brothers/uncles of all the women in the family. This was an extended sea-faring family on a sea-faring island in a sea-faring nation and therefore any other career was basically heresy, especially for a first son.

Originally composed just a few fishing villages on a sandy spit of land, the residents of Fanø bought the island from the Danish king in 1741 and began their own independent maritime industry. From 1768 to 1896, a total of around 1100 ships were built and manned out of Fanø’s harbor, with these ships and their cargo sailing the globe (my extended relatives died anywhere from Indonesia to Chile). A change in construction technology and the gradual silting of the harbor made it impossible for Fanø to compete with bigger shipping ports at the turn of the 20th century, and the golden era eventually wound down…probably around the time that my grandfather was growing up, giving him the idea that perhaps there were other career fish to fry, as it were.

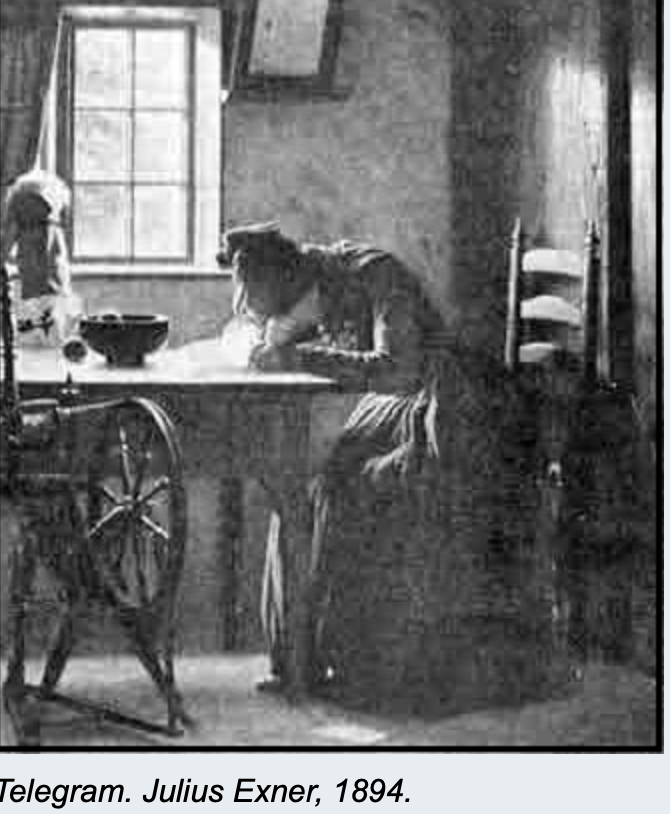

One must by needs now turn one’s attention to the lives of the women who married all these captains and seamen. A local statue in one of the two graveyards on the island gives a good clue:

I visited Fanø in 1984 and visited the museum there, which gave me a tremendous and somewhat bittersweet insight into the lives of the island’s women. The yearly calendar went like this:

In November, the ships returned. The busy winter season of repairs and replacement of all needed parts began. In December, the holidays were a joyous time of celebration and relaxation. In January and into February, weddings took place, and in March, the ships set sail again. For the rest of the year, the women planted the potatoes and wheat and cared for the children. And waited. And waited. And waited.

While Fanø has a lovely and unique local dressing tradition, I was most touched by the exhibit of the widows’ wardrobe. There was one outfit one wore for the first six months after one’s husband died, a second for the second six months, and then a third that one usually wore *for the rest of one’s life.* Some widows were lucky enough to scoop up an available widower, but that was by no means guaranteed. Long lives of hoping and serving seem to have been the norm:

Itinerant father aside, what this all leaves me with is a deep appreciation of generations and centuries of tough lives breeding tough relationships with tough people who endured difficult weather and challenging situations. But I also in the process have grown to admire and appreciate my grandfather all the more, who turned his back on this cold constricted life and chose to go a different direction by setting sail, as it were, for a new profession in a new land. I only wish I could have known him, even just a little bit. And I’m sure my father felt the same way and would have benefitted greatly from his counsel.